The Eight Cognitive Processes

Delineating the History and Contemporary Theory of Carl Jung's Psychological Types

The History of Psychological Types

C. G. Jung’s living legacy can broadly be placed within two psychological paradigms: that of depth psychology, a study of human experience with an emphasis on working with the unconscious and its dynamics, and that of psychological types, descriptions of cognitive and behavioral inclinations that operate close to conscious awareness.

Jung began conceptualizing this latter typology in part to grasp the irreconcilability he saw in Sigmund Freud’s and Alfred Adler’s own psychological theories. Jung’s inquiry, with the help of his friend Hans Schmid and the original contributions of analyst Maria Moltzer and Jung’s ‘spiritual wife’ Toni Wolff1, grew into psychological types. While initially hesitant to posit a plurality of truth, Jung came to see how “every judgment made by an individual is conditioned by his personality type … every point of view is necessarily relative.”2 His typology captures how these biases tend to operate.

Following the publication of Psychological Types in 1921, Jung’s subsequent work largely focused on elucidating more esoteric and mystical subjects. As his typology caught on, he distanced himself from its popular applications, comparing them to “a childish parlour game.”3 Jung nevertheless continued to use his typological theories in his private practice, still finding it integral as a “psychology of consciousness”4 that supplemented his inquired inward and downward towards spirit.

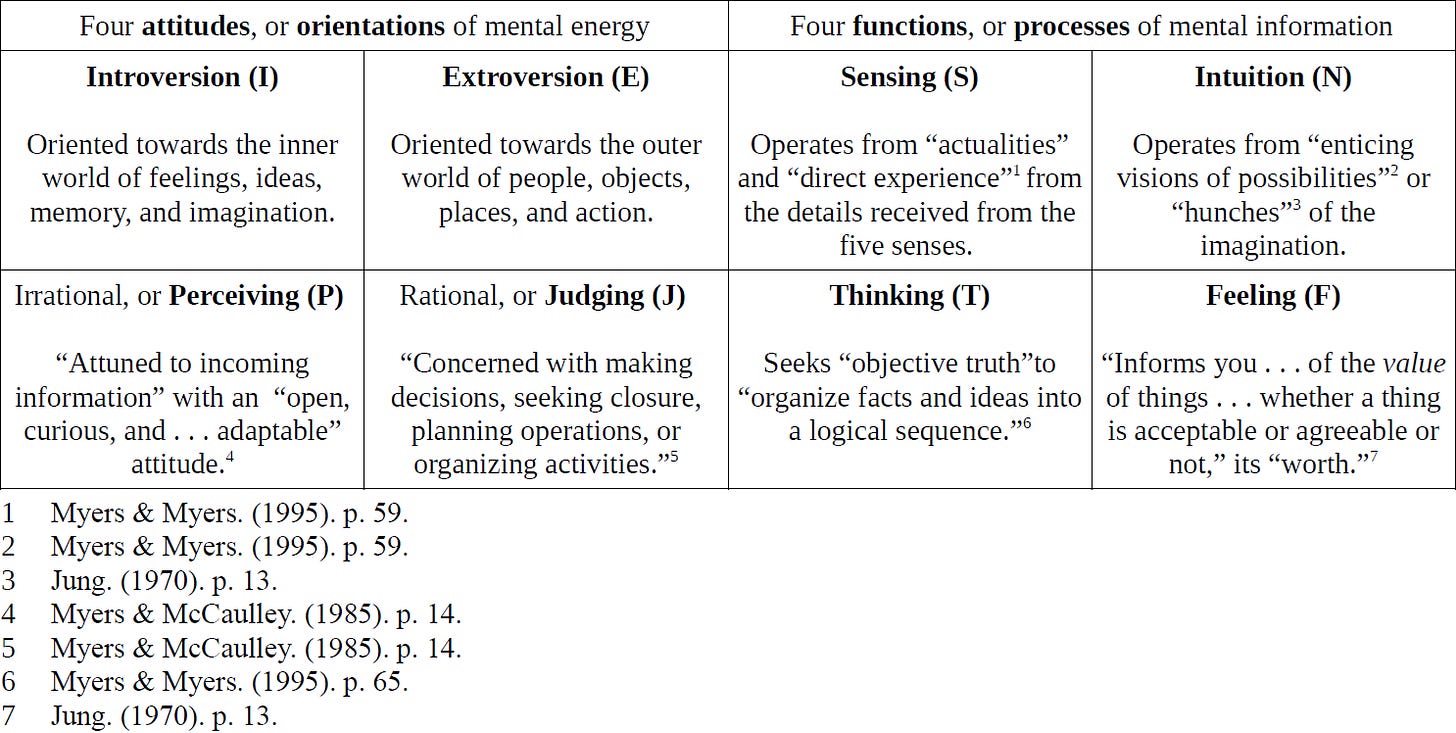

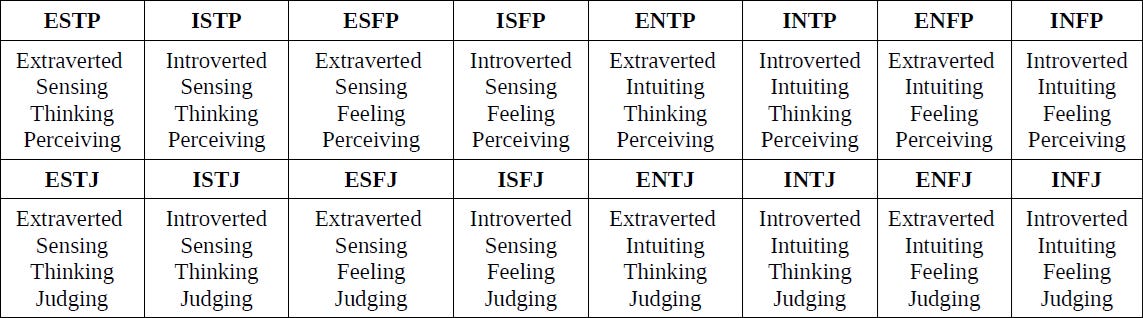

Contrary to his preferences, Jungian typology has become an internationally acclaimed tool in both professional and hobbyist fields of business, counseling, coaching, and psychotherapy. The success of psychological types is in no small part a consequence of Isabel Myers’ and Katharine Cook Briggs’ operationalization of Jung’s ideas, Isabel’s own amateur psychology research converging with Jung’s. Through the latter half of the 20th century, they worked to further clarify and formalize Jung's original ideas, creating an assessment tool and framework that emphasizes accessibility and practical utility for understanding and developing oneself or others. Jung’s typology has inspired many other type iterations,5 although the most successful tend to follow the precedent set by the focus of the Myers-Briggs Type Inventory: the eight ‘functions’ and ‘attitudes,’ and the sixteen personality types they produce:

Despite its popularity, types remain outside of mainstream psychology, often derided for its essentializing of human nature. The current scientific paradigm, grounded in centuries of success privileging the explanatory power of the mechanistic and physical over the teleological and typological, assumes innate behavior and cognitive development should be attributable to specific genes, hormones, evolutionary processes, and/or neurology. Likewise, psychological modeling should follow the evidence, abstracting from emergent averages in the data along spectra and scales, not emphasizing immaterial binaries that depend on subjective generalizations and geometric elegance.

At the same time, acclaimed researchers McCrae and Costa Jr. of the Big Five personality traits, the gold standard in personality models, find “each of the four indices [of type] showed impressive evidence of convergence with one of the five major dimensions of normal personality.” Jungian extroversion parallels Big Five extroversion; intuition corresponds to openness to experience; feeling relates to agreeableness; judging is similar to conscientiousness; and neuroticism has no match.6 McCrae and Costa view type as a “set of internally consistent and relatively uncorrelated indices” with “no lack of correlational data” if type were reimagined as an open inventory of traits opposed to the closed, typological model that it is.7

These criticisms point to the irrevocably pattern- and process- focus of psychological types, comparable to the qualitative inquiry of dynamical systems.8 Its pairings of functions and attitudes exemplify the Heraclitian principle of enantiodromia that Jung favored, everything giving rise to and most knowable through its tension with its polar opposite, forming compensatory dualities and quaternities.9 There is no wholly physicalist basis for these complementary pairings, nor explanation for why their integration is fundamental to the process of becoming psychologically whole.

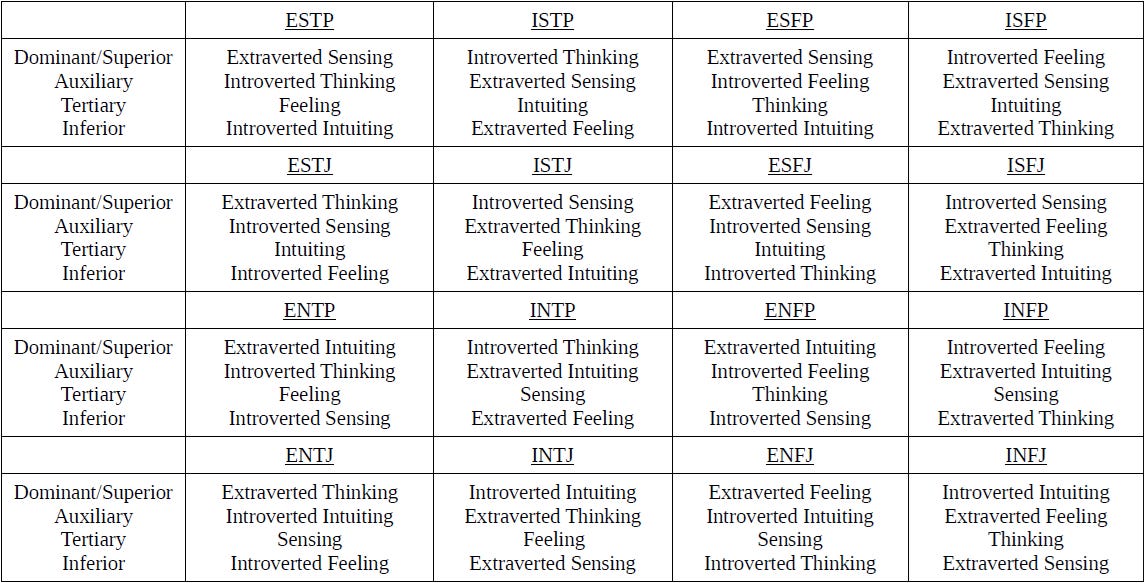

Further straining psychological type’s relationship with science and academia proper, the orientations and mental processes outlined above are viewed by many type theorists as supplemental and superficial compared to what is argued to be at the core of the theory underlying Jungian types10: the eight cognitive processes:

Also known as attitude-functions, cognitive functions, and mental processes, the cognitive processes represent eight essential dynamics of perceiving or understanding the world. They are a combination of Jung’s better known attitudes/orientations (introverted and extroverted) and functions/processes (feeling, sensing, thinking, intuiting), but represent the emergence of something markedly different and more aligned with the phenomenological experience of consciousness than the behavioral focus of much thought and research addressing the attitudes and functions in themselves.

While many Jungian typologists join academic personality researchers in their rejection of cognitive processes for their “speculating”11 into human cognition, dependence on anecdotal evidence, and lack of statistical validation,12 they remain widely popular for their accessibility, practical applications, and elegance, with many theorists arguing the processes “are truly the building blocks of personality,”13 reflecting how the “psyche is dynamic and is always seeking balance.”14

Jung originally theorized that everyone has an innate preference for one of the eight processes. This dominant or superior process is in turn easiest to use, the most reliable and generative, and initiates and directs the individuation process. In addition, Jung believed everyone had a less differentiated and complimentary auxiliary process that supports the dominant process,15 and an inferior process that is the inverse of the superior process.

Subsequent research into cognitive processes, following the accessibility and utility set by Myers and Briggs, have evolved Jung’s work into more standardized four- and eight-part hierarchical “stacks” of processes, assigning a particular set of attributes to each position in addition to the characteristics of the cognitive process assigned to it. Preliminary electroencephalogram (EEG) research by Dario Nardi shows some correlation between neocortical activity and the dominant cognitive process16 and general evidence of a secondary process, following Jung’s original supposition, while the totality of stack models of cognitive processes has yet to be validated.

From Jung onward, a fourth inferior process continues to be proposed in opposition to the superior process. Jung asserts that the inferior function is permanently in a state of underdevelopment, “otherwise we would be perfect like God, and that surely will not happen.”17 Theorists generally interpret the inferior process as difficult to develop, associated it with one’s shadow, the unconscious, and/or the anima or animus, and see it as key to transformative self-development.

The Theory of Cognitive Processes

For the sake of clarity, I describe each cognitive process as it is defined in a dominant role in the psyche. Synthesizing various texts by professional typology and Jungian theorists, I summarize each process's unique mental experience and expertise that generally constellate a normative set of attitudes and beliefs among those who prefer using the process. These descriptions are built from Leona Haas’s and Mark Junsiker’s Building Blocks of Personality Type, Gary Hartzler’s and Margaret Hartzler’s Functions of Type, Dario Nardi’s 8 Keys to Self-Leadership and Neuroscience of Personality, and Personality Type: an Owner’s Manual by Lenore Thomson.

Each cognitive process is introduced by its name, and the two personality types for whom it is a superior process.

The Perceiving Cognitive Processes

These first four cognitive processes are modes of perception—“how we access data and focus attention”18—which Jung called “irrational,” “not as denoting something contrary to reason, but something beyond reason, something, therefore, not grounded in reason.”19

Introverted Sensation (Si; superior for ISFJ, ISTJ)

Those who are the dominant introverted sensation type perceive through a vast reservoir of rich sensory details and memory, automatically comparing what is in the present moment with past experience, noticing any minute concrete differences from past precedent. Their memories can be as vivid as their initial experience, becoming condensed, valued foundations for processing the present and planning for the future. They have a heightened awareness of their physical constitution, such as their energy or hunger levels. As a consequence, they prefer operating from standards that best keep them comfortable: what is personally familiar, or what has been widely established as a reputable. They are inclined towards what has stood the test of time, such as traditions and customs, social duties and obligations, and roles in which working sequentially and with expertise gained through rote repetition make them respectable members of their community. Through a commitment to what is known to work, following role models and authorities, and acting carefully to maintain and honor the structures of society, introverted sensors aim to build roots and erect barriers to prevent unforeseeable problems caused by the constant flux of life. In turn, they prefer working slowly and steadily towards their objectives, remaining sensitive to any anomalies that violate the stability of what is known. They may become overly cautious and averse to new experiences, holding their desire for security and predictability above making necessary changes in life.

Extroverted Intuition (Ne; superior for ENFP, ENTP)

Those who are the dominant extroverted intuition type perceive through emerging patterns and dynamics, quickly connecting the dots of their present context and their experiences or ideas, generating alternative possibilities to what is accepted as fact by themselves or others. They follow their curiosity and hunches to explore tangents wherever they may take them, brainstorming spontaneously and impartially without immediate concerns for utility or relevance. As a consequence, they prefer operating from a variety of inputs, particularly what is novel and stimulating, or piques their imagination and humor. They are inclined towards roles that keep them inspired, allowing them to be inventive and operate outside the box. At best, their divergent thinking may converge on original insights that may shift present dynamics or catalyze a change. Extroverted intuitives often become pioneers of new ideas or technology, excited by untapped potentials for innovation. In turn, they are apt to use their enthusiasm and optimistic idealism to promote or champion causes that may be revolutionary. They may become too engrossed in hypotheticals for their own sake, fail to make decisions, complete projects, or stick to commitments, holding their desire for novelty above boring and stifling routines.

Extroverted Sensation (Se; superior for ESFP, ESTP)

Those who are the dominant extroverted sensation type are immersed in their perception of their present situation, developing a strong memory for details in context. They are stimulated by sights, tastes, sounds, movement, and richness of the environment surrounding them; tracking where things are moving and heading; noticing subtle changes in the moods and behaviors of others and the motives they suggest. Enjoying the here and now matters most to extroverted sensation types: they take life as it comes, becoming one with their environment, taking time to “smell the roses.”20 They value aesthetic harmony for its sensual pleasure, and activities that keep them energized, such as athletics. They are in tune with their gut reactions and impulses for seizing opportunities, rising to challenges, testing limits, or acting quickly if a crisis presents itself. As a consequence, they often strive to remain current, in sync, and on the pulse of their fields of interest, learning the nuances and mannerisms, and adopting the standard style and tools to keep up appearances. By absorbing such conventions and familiarizing themselves with paradigmatic norms and popularity, extroverted sensors become skillful improvisers and multi-taskers who can leverage their acculturated knowledge to make a strong impact as an insider. They may become overly impulsive and reckless in their behavior, overindulgent in sensory pleasures, or fail to consider anything that is not concrete or outside the present moment.

Introverted Intuition (Ni; superior for INFJ, INTJ)

Those who are the dominant introverted intuition type perceive through a meta-perspective that implicates deep meaning beneath or behind concrete experience. They come to know things by closing off from the external world and receiving flashes of insight, perceiving symbols and images that emerge seemingly from nowhere, reconciling disparate viewpoints into a greater whole that is sometimes premonitory in nature. Reality is limited by the perspectives through which it is approached, therefore introverted intuitives seek hidden angles to transform their perception, and as a consequence themselves. Insights cannot be willed: they require the right conditions or provocations to release them from the depths of their mind. Because totalized perspectives and metaphysical understanding come to them easily, introverted intuitives are interested in contemplating ultimate questions about life, death, and meaning, often coming to conclusions they struggle to articulate. Therefore, they often keep insights to themselves, despite the confidence they may or may not feel in their perceptions. At best, introverted intuitives fill the roles of visionaries who transform society with their vision of what feels ultimately true. They may become obsessed with fantastical world views that disconnect them from others or society, neglecting everyday practical needs and decisions that require concrete responses.

The Judging Cognitive Processes

This second set of cognitive processes are “how we organize and make decisions,”21 which Jung called rational, or “that which accords with reason.”22

Extroverted Thinking (Te; superior for ESTJ, ENTJ)

Those who are the dominant extroverted thinking type operate with control and results in mind, in accordance to evidence-based metrics and criteria that allow them to act decisively and optimally. They prefer using data that can be objectively measured and quantified for the maintenance and improvement of their tasks and plans. Analyzing the world and locating inefficiencies comes easily to extroverted thinkers, as does setting priorities and creating step-by-step methods to reach concrete goals. They often focus on mechanics and causality, not wanting to waste limited resources and time on whims, speculation, or details: decisions are best when reduced to black and white, or cause and effect. Likewise, they are concise communicators who focus on the logical consistency of their own and others' reasoning to persuade others and reach conclusions. They are often both strategically and tactically skilled, and can quickly recognize the scope of problems and generate solutions to them, making them effective managers and leaders who enjoy rising to challenges, setting courses of action, implementing multi-faceted plans, and maintaining performance standards for themselves and others. They may become overly controlling of others in their imposition of rules, dismissing any negative feedback or distractions that ultimately may be pertinent to their objectives, or ignore complexities in a unilateral search for simplicity.

Introverted Feeling (Fi; superior for ISFP, INFP)

Those who are the superior introverted feeling type make decisions in alignment with their deeply felt personal values and conscience. They experience strong reactions concerning what matters to them most, and have a profound need for internal harmony and moral integrity, even when their values are not fully conscious. Their values feel self-evident and absolute, and so they often avoid discussing controversial issues, assuming theirs and others' convictions would not change or benefit from the exchange. At the same time, they are skilled listeners, highly attuned to subtleties communicated by others, including tone and word choice, noting when others are trying to hide something, or experiencing internal turmoil. They highly value honesty and authenticity, and are willing to defend desires and beliefs when they do not harm or impose on others. They tend to extend this tolerant attitude broadly, preferring to be free to live according to their own beliefs, and expecting the same of and from others. Introverted feelers prefer interacting with others on a one-on-one basis, emphasizing the uniqueness of individual motivations and convictions, opposed to conforming to normative social behavior. They may become closed off from people they feel violate their sense of right and wrong, or choose not to articulate or share their values with others, even those to whom they are close.

Introverted Thinking (Ti; superior for ISTP, INTP)

Those who are the dominant introverted thinking type come to understand a subject by detaching from the particulars and evaluating it in terms of various frameworks and principles that they have internalized. They actively classify and categorize the world around them, figuratively or literally taking things apart to understand their components, sometimes applying multiple models at once to maximize the accuracy and clarity of their determinations. They have a curiosity for understanding how things work on a deep level, putting great effort into defining things precisely and refining existing models as new data requires it. They strive to bring elegance to their understanding, “maximizing explanatory power with minimum complexity,”23 in order to create leverage points of minimal effort for maximum effect. They are compelled to follow any logical inquiry to its conclusions, regardless of their reasoning's discrepancies with conventional values or preconceived criteria of true or false. As a consequence, they are skilled at creating original models for understanding the world and critiquing preexisting ideas for improving their internal consistency. They may not accept things that fail to fit within their models, overextending their ideas beyond their appropriate scope, or fail to consider the concrete consequences of their impersonal ideas.

Extroverted Feeling (Fe; superior for ESFJ, ENFJ)

Those with dominant extroverted feeling tune in to the needs and values of others. They can read the emotional energy of a room or group and adjust their behavior accordingly, coming to decisions to maintain and create social harmony. They are inclined towards considering the needs of the collective in terms of commonly-held values; likewise, they are known for operating from social norms as a foundation for developing amiable interactions and maintaining standards of politeness. At the same time, they are driven to interact with people as individuals and are apt to empathize with others’ perspectives, disclosing their own values to prompt others to share theirs, often taking on others' needs as their own. Extroverted feelers frequently feel compelled to take on causes or roles to help or defend others, through which they can discuss and cultivate strong social networks. As a consequence, they are skilled at generating a sense of oneness and intimacy with individuals or among groups, producing a congeniality that makes them great hosts and facilitators, or by creating safety that allows for vulnerability and the resolution of conflict. Their desire to help may become excessively imposing, crossing personal boundaries or forcing superficial values and norms on others. Alternatively, they may sacrifice their needs for others and become dependent on others' affirmation.

References

Beebe, John. (2017). Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type. Routledge.

Bennet, Angelina. (2010). The Shadows of Type. Lulu.

Haas, Leona, & Mark Hunziker. (2014). Building Blocks of Personality Type. Eltanin.

Healy, Nan Savage. (2017). Toni Wolff & C.G. Jung: A Collaboration. Tiberius Press.

Hartzler, Gary, and Margaret Hartzler. (2005). Functions of Type. Telos.

Hunziker, Mark. (2016). Depth Typology. Write Way.

Jung, C. G. (1976). Psychological Types. Translated by H. G. Baynes. Revised by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1970). Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice (The Tavistock Lectures). Vintage.

Jung, C. G. (1989). Memories, Dreams, Reflections, edited by Aniela Jaffé. Vintage.

Kiersey, David. (1998). Please Understand Me II. Prometheus Nemesis Books.

Myers, Isabel and Peter Myers. (1995). Gifts Differing. Davies-Black.

Myers, Isabel. (1985). A Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologist Press.

McCrae, Robert & Paul Costa Jr. (1989). “Reinterpreting the Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator From the Perspective of the Five‐Factor Model of Personality.” Journal of Personality 57, no. 1 (March). pp. 17–40.

Nardi, Dario. (2005). 8 Keys to Self-Leadership. Unite Business.

Nardi, Dario. (2011). Neuroscience of Personality. Radiance House.

Quenk, Naomi. (2001). Was That Really Me? Davies Black.

Reynierse, James. (2009). “The Case Against Type Dynamics.” Journal of Psychological Type 69, no. 1 (January): pp. 1–24. https://www.capt.org/research/article/JPT_Vol69_0109.pdf.

Thomson, Lenore. (1998). Personality Type: An Owner’s Manual. Shambhala.

Von Franz, Marie-Louise & James Hillman. (2013). Lecture on Jung's Typology. Spring.

Healy. (2017). pp. 177-183.

Jung. (1989). p. 209.

Jung. (1976). p. xiv.

Jung. (1989). p. 209.

Post-Jungian typology includes the highly systematized Socionics model of the Lithuanian psychologist Aušra Augustinavičiūtė and her followers, neurological correlations studied by anthropologist Dario Nardi, four-function hierarchical models of Naomi Quenk and others, John Beebe’s eight-archetype model, and David Keirsey’s four temperaments and behaviorally-focused research.

McCrae & Costa Jr. (1989). pp. 32-33.

McCrae & Costa Jr. (1989). p. 19; p. 23.

Typologist Dario Nardi hypothesizes that psychological types are examples of strange attractors: irreducible, non-material patterns that can emerge from chaos. (2011). p. 11.

Jung. (1981). p. 178: “There is no consciousness without the discrimination of opposites.”

This is suggested by Catherine D. Myers in Leona Haas & Mark Hunziker. (2014). p. xvii.

Kiersey. (1998). p. 30: “I have never found a use for [the] scheme of psychological functions, and this is because function typology sets out to define different people’s mental make-up—what’s in their heads—something which is not observable, and which is thus unavoidably subjective, a matter of speculation, and occasionally of projection.”

For a thorough rebuke of cognitive processes, see James Reynierse. (2009). pp. 1–21.

Haas & Hunziker. (2014). p. 2.

Hartzler & Hartzler. (2005), p. 3.

Jung. (1976). § 668: “Experience shows that the secondary function is always one whose nature is different from, though not antagonistic to, the primary function.”

Dario Nardi’s Neuroscience of Personality is his first book on these correlations between EEG scans and personality types, which suggests that dominant processes have distinct resting and “flow” states, with some activity suggesting the auxiliary process.

Jung. (2014). pp. 97-98.

Nardi. (2011). p. 74.

Jung. (1976). § 774

Haas & Hunziker. (2014). p. 41.

Nardi. (2011). p. 74.

Jung. (1976). § 785.

Nardi (2011). p. 106.